PART THREE

Mrs. White ran a rooming house off the downtown square that was once a grand mansion, one of the few old homes that had escaped Huntsville’s wrecking ball. When we arrived, Mrs. White greeted us sweetly like the innocent broad we knew she wasn’t. I had the Dear John letter in my pocket but didn’t pull it out until Pistol and I accepted her offer of lemonade and teacakes.

“What a homey old broad,” Pistol whispered, his lips dusted with powdered sugar. “You’d never know she’s got somebody buried in the backyard.”

“Mrs. White, tell us what you know about this,” I said and shoved the letter under her nose. “It was in John D. Boddy’s pocket the night he was snuffed.”

She took out the letter and squinted at it. “I need my glasses. Won’t you come inside?”

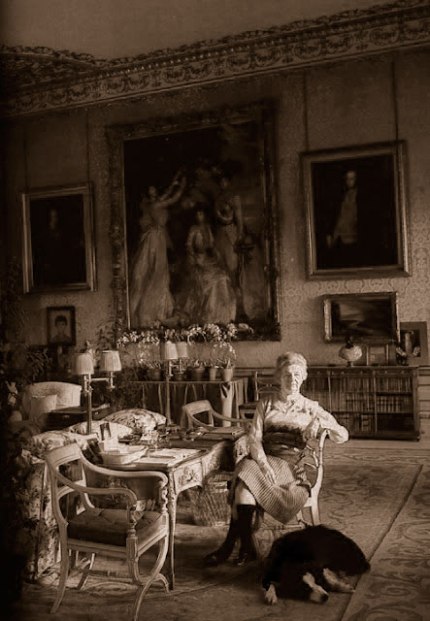

So we followed our prime suspect into the foyer of the old mansion. What a sight it was, too—massive paintings, dusty antiques and mounted animal trophies on the walls, and a marble staircase leading to a second floor of well-appointed rooms.

As we entered, Mr. Green was skipping down these stairs in a white tennis sweater and white trousers, his jacket slung over his shoulder.

“What are you doing here?” I said.

Green flashed a blinding smile. “I live here. We all do.”

“That’s right,” said Mrs. White. “Mr. Green is in the Conservatory. Miss Peacock is in the Billiard Room, Professor Plum has the Study, Miss Scarlett is in the Lounge, and Col. Mustard-Lighthouse has appropriated the Dining Room.”

“Where are you?” I said.

“I have the Ballroom,” Mrs. White said. “The best room in the house.”

“Say, where do you think you’re off to, whippersnapper?” Pistol said, grabbing Mr. Green’s arm before he could dash out the door.

“A Wendy Davis rally,” said the eager young politician. “Unhand me before you muss my sweater.”

Then, through the bank of windows overlooking the backyard, we saw four mounds of freshly turned earth.

“What’s that?” I said.

“Oh, another one of Professor Plum’s backyard projects,” Mrs. White said absently as she searched a small secretary for her glasses. “He fancies himself a landscape designer.” At last she found them and put them on. Clucking her tongue, she read the rancid Dear John letter that Sarah had written.

“It was mailed here,” I said.

“I’ve never seen it before,” she said and shuddered as she refolded the letter and slipped it into the pocket of her apron. “Nasty business.”

Then Miss Scarlett burst into the room and, before she noticed Pistol and me, blurted out: “You’ll never guess—” Then, blanching a little, she said, “Oh, hello, detectives.”

Mrs. White played the good hostess. “You remember Detective Splendor and—”

“They call me Pistol,” Pistol said, jamming both fists in his pockets. He threw a look at me that said: “Now’s our chance to sweat these dames.”

“You’ll never guess what?” I said, which flustered Scarlett. She blushed. “Only that it might rain,” she said.

“And that would be good for the Professor’s little project,” said Mrs. White, leading us back into the kitchen. “Hydrangeas.”

Then, as he peered through the kitchen windows, Pistol saw something suspicious. “Someone’s in the backyard—and it doesn’t look like one of the inmates of your little asylum.”

“Oh, dear,” said Mrs. White, clasping her hands under her chin.

“You go get a look-see outside while I search the place,” I told Pistol, and he drew his revolver as he slipped out the back door.

So Pistol and I split up, leaving the two women in the kitchen. I went from room to room in the mansion, opening the doors to their wardrobe closets, rifling through their bureau drawers. I ended up in the cellar, and then I found what we’d come for. Muddy shoe prints led from the cellar door to a small dark lair lit by the dim light of a small window. The last home of Fractal Bob. I stepped in and closed the door behind me.

Nobody had cleaned up in here for years. The small iron bed had been slept in, there were bottles of booze everywhere, and ashtrays full of butts from smokes of different brands. The small typewriter had a broken ribbon. The wire basket was full of half-written trifles and false starts. The desk drawers had been pilfered, no doubt of everything Fractal Bob had owned. I turned on the desk lamp, and there it was, a telltale bullet hole in the door and a pockmark in the concrete above the bed. I got down on the cold floor, glad I’d remembered my flashlight. I’d just found the bullet when I heard someone in high heels running down the cellar stairs. It was Miss Scarlett. “Come quick,” she said breathlessly, a lock of blond hair falling over one eye. “Something’s happened to your detective!”

. . .

Pistol was slumped in a chair with an ice pack on his head when I got back to the kitchen. His crumpled hat sat on his lap. “Well, tell me you at least got a good look at him.”

“Better than that. He’s lying in the backyard. See for yourself,” Pistol said.

I threw open the back door, but the yard was empty. “Hit him harder next time, stupid. He’s gone.”

“He’ll be back,” said Pistol, pulling something from his pocket. “I got his wallet.” And then something from the other pocket: “And his gun.”

“You get a name before he clobbered you?” I said.

“We’ve met him before,” Pistol said, “the other night at the cemetery.”

“Ah, yes,” I said. “The gunsel with the funny name.”

“Oh, my goodness. What a lot of excitement,” said Mrs. White, dropping into a kitchen chair. Miss Scarlett hurried to her side, fanning her with a hanky. But this was all for show. I was beginning to think the old broad’s specialty was trouble.

All of a sudden Mrs. White was on her feet and out the back door, clapping her hands. “You, there! Ward Three! Shoo! Shoo!”

I rushed out in time to see a big black dog, the one we also met in the cemetery, run around the side of the Carriage House and into the trees behind the mansion.

“What’s that you called him?” I asked Mrs. White.

“Why, Ward Three, dear. That’s his name.”

“Your dog?”

“Oh, my goodness, no. He’s everyone’s dog. A good watchdog he is, too. I just didn’t want him digging up Professor Plum’s hydrangeas.”

We stepped inside to find that Miss Scarlett had poured Pistol a big glass of bourbon. His head was feeling a lot better. “What’s the story?” said Pistol. “You find anything upstairs?”

“Upstairs, downstairs.” I turned to Mrs. White. “Bring everybody back here. Everybody who’s mixed up in this case. We’re going to shake them all up, see what we get.”

“Do you know who killed my Bobby Baby?” said Miss Scarlett.

“Indeed I do.”

“Do you really?” said Mrs. White. “Well, if you’ll excuse us, we’ll see if we can round them up.”

The two women left us, eager to have a word out of our earshot.

I nudged Pistol. “Let’s get something to eat. I’m thirsty.”

“Well, Splendor, how you gonna to do it?” he said.

“I haven’t the faintest idea. I’m just going to look and listen and pray that somebody makes a slip. Just one slip,” I said.

. . .

Pistol and I lingered just outside the Drawing Room as Mrs. White, Miss Scarlett, Professor Plum, Col. Mustard-Lighthouse, Mr. Green and Miss Peacock took their seats around the room.

“What’s the plan?” Pistol said.

“Build up a case against each of them. Throw everything we got at them and throw it hard enough to bounce,” I said. “Stay sharp. If anything bounces, you need to be the one who catches it.”

Pistol tugged on the brim of his crumpled hat. “You can count on me.”

“You warm up the room,” I said. “I left something upstairs.”

When I got back, the natives were already restless.

“Get on with this, copper. I’ve got places to go and people to meet,” Green said.

I started with the loquacious Miss Peacock, who had just poured her first drink.

“When did you last see Fractal Bob?”

“I’ve already told you. I’ve never seen Fractal Bob,” she said, dark eyes dancing with the mirth of some joke I didn’t get.

“You own a gun? A .22?”

“Doesn’t every girl?” Peacock said.

“Have you ever fired it in this house?”

“Of course not. But—” Peacock paused, looking uncharacteristically discreet.

“But what?” I said.

“It was Mr. Green.”

Green stood up indignantly. “I’d never carry a .22. What’d you take me for. Some kind of pansy?”

“It wasn’t Mr. Green, was it?” I said. “But why did you say so?”

“He always seems guilty of something,” she said, tossing back her second.

I pulled a .38 from the pocket of my trench coat and laid it on a round table. My suspects gasped. “That’s not mine,” Green said. “Mine’s upstairs. I’ll get it if you want me to.”

“That won’t be necessary. What about you, Miss Scarlett?”

“The only .22 in the house belongs to Peacock,” said the full-lipped blonde. Her hands trembled as she lit a cigarette.

“But I didn’t kill anyone, least of all Fractal Bob,” said Peacock.

“The other night you all swore you didn’t know this character, Fractal Bob,” I said and they quickly assured me that that was true. “How can it be when he’s been living here, too?” And then I looked from face to face to see how they took the news. Peacock and Green had gasped, but the others were anything but nonplussed. The two women, White and Scarlett, edged closer together. “But of course you knew that, didn’t you, Mrs. White? You rented him the room.”

Professor Plum turned on Peacock with belittling amusement. “Some sleuth you are. Skulking around Forest Hills, hiding behind bushes, peeking in windows, when all along Lover Boy was right here under our noses. The whole time!”

I turned my gaze on White, who was wringing her hands. “Not the whole time. Right, Mrs. White?”

“I let him move into the cellar room—my, it must have been three years ago—when his parents kicked him out. They found his political tracts, you see. But nobody else knew.”

Professor Plum raised his glass of whiskey in an arrogant little salute. “Oh, I knew. One night I followed a tall figure in a trench coat and fedora here after I’d happened upon him delivering his tracts. But I never said a word. I’d been sworn to secrecy.”

“Balderdash, Plum,” said Col. Mustard-Lighthouse.

“Au contraire, Lighthorse or whatever your name is. Fractal Bob and I had quite a friendship—all by post, of course. I was his muse and his most significant influence. My thoughts became his,” Plum said, still smiling with condescension. “He was my protégé until his madness and insecurities got the better of him.”

Miss Scarlett pointed a finger at Plum. “I’ll not let you say my Bobby Baby was mad.”

“Face it, Scarlett,” said Plum, grinning incessantly. “He was barking, disturbed, crazy, plum loco. Ask Peacock. She drove him to it.”

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” Peacock said. “Bob and I were the best of friends. Better than friends, if you know what I mean.”

Scarlett sucked in her rouged cheeks. “That’s what you think, sister.”

Green lifted his arms in exasperation. “Oh, for crying out loud! It’s Mrs. White and Miss Scarlett. They’re ‘Fractal Bob,’ always have been.”

“There’s a stiff in the morgue that says you’re wrong,” I said. “Am I right, Mrs. White?”

“Well,” she said, “I don’t know who that is. But I can promise you it’s not Fractal Bob. Fractal Bob is very much alive.”

“Here we go again,” Green said. “Somebody pour me another drink.”

Just then we heard a scuffle in the foyer, and Pistol opened the door to a gaggle of cops who held the arms of a large man, struggling to get free.

“Sit,” I commanded and the officers dumped the gunsel in a chair.

“Johnny Stompanato,” Pistol said, glaring. “Here’s the one who jumped me in the backyard this afternoon.”

Johnny Stomp let loose a loud guffaw and I smacked him. That shut him up.

“Last night you asked me to check the stiff in the morgue for a tattoo. ‘No, tattoo, no Fractal Bob.’ What was the tattoo?” I said.

“Lady Echo,” Stomp said. “Says ‘Lady Echo’ on his arm. The sap.”

“Who do you know with that tattoo?” I said.

“Not on your life, sister. I’m paid good money to keep my yap shut,” he said. “Let’s just say he’s flown the coop, and everybody’s better off.”

Peacock looked up, eyes misty with excessive drink. “You mean there really is a Fractal Bob?”

“Not no more,” Stomp said and he laughed again.

“It seems you have jumped the shark here,” said Professor Plum, his nose swollen and cheeks blushing with the warmth of a third whiskey. “Who are all these unnecessary characters and the extraneous headless stiff in the morgue? Why, this is as long as one of my columns, maybe even longer.”

Stomp jabbed a fat finger in Plum’s face. “You’re just jealous. Admit it.”

But the Professor was still smiling. “I’m no such thing. I’m a well-established writer of Northern credentials with a solid following. What do I have to be jealous about?”

“That’s rich,” muttered Miss Scarlett.

Plum’s face suddenly went slack, the smile gone. “Careful, dear. These good detectives might want to know what other young lady in the house has been packing a .22.”

I looked at Pistol. “Looks like we’ve stumbled on a little triangle here.”

“Oh, don’t be ridiculous,” Scarlett said. “The professor is twice my age.”

“But Bobby Baby was just right in every way,” I said. “Too bad he didn’t even know you existed.”

Scarlett bristled and who should come to her aid but Johnny Stompanato. “Oh, he knew she was alive, all right. Tell them, Lady Echo. No? OK, then I will. They were pen-pals and lovers, right up until the night she shot him.”

Green leapt up, surprisingly agile for a drunken man. “I knew it!”

“Sit down, you idiot,” said Scarlett. “You thought I was Fractal Bob.”

“So you admit it,” said Pistol, and Scarlett began to cry. “Yes, I shot Bobby Baby.”

“You shot at Bobby Baby,” I said. “You didn’t hit him. I found the bullet from your gun under his bed. It pierced the door and hit the wall. But there wasn’t a single drop of blood.”

“But why? Why did you shoot our Frackie Bobby?” Miss Peacock said slurringly.

I turned on Plum. “That’s a question for the Professor.”

Plum smiled again, his eyes as blue as gas jets. “I had nothing to do with it. I don’t even own a firearm.”

“You didn’t need one. You sent your love-sick little accomplice to do the deed. The two of you were both writing him letters, but he wouldn’t let either one of you get close to him,” I said. “So you sent her to his room, knowing if he’d open the door to anyone, it would be a leggy blonde with a figure that won’t quit.”

Johnny Stomp nodded his head, which was the size of a canned ham. “The stupid sap.”

Plum laughed. “You’ve got this all wrong, detective. I could have tricked her if I’d wanted to, but I didn’t send anyone.”

Mustard-Lighthouse had roused himself. “He’s finally telling the truth. Plum can’t even get the maid to take out his trash. I did it. I sent her.”

“Why on earth?” said Mrs. White.

“Minerva, dear,” said Mustard-Lighthouse, “we couldn’t afford the risk of having a new voice out there we couldn’t control. He might have said anything. Think of it. It was mildly amusing when he was on our side. But what if they had gotten a hold of him?”

“They who?” I said.

“He means The Powers That Be,” said Plum. “That’s what I call them.”

White was fuming. “I had it well in hand, Albus. You should have left it to me. We’d still have Fractal Bob and not these—“

“These what?” I said.

“Hacks,” Pistol said. “A committee of hack writers who pale in comparison to the real deal.”

“I get it,” Green said. “The real Fractal leaves and the old lady takes over.”

“You’re half right,” I said. “Mrs. White began recruiting Faux Fractals to keep the franchise going. She used Miss Scarlett to lure them in.”

“Yeah, every moonstruck poet from here to Austin,” Stomp said, and then something on the table caught his eye and he lunged for it. “My gun!”

But before he got his beefy hands on it, the officers caught him and wrestled him back into the chair. I dangled the .38 in front of him. “This is the murder weapon, the gun that killed John D. Boddy and who knows who else.”

“You can try, lady copper, but this rap won’t stick,” Stomp said. “You know who I work for.”

“I don’t care,” I said and then I stepped outside to fetch the piece of evidence I’d recovered from upstairs, a birdcage covered with a purple velvet drape. “The one who owns this is going to sing like a canary and put the both of you away.”

I yanked off the veil and inside the cage was Boddy’s skull. Miss Scarlett screamed. But the Professor was smiling again. “You can’t prove that belongs to Boddy. I have twenty-seven hours toward a master’s degree in anthropology. I have artifacts such as this all over my room.”

“And in the four shallow graves in the backyard,” I said. Then I put my two lips together and blew. At the sound of my whistle, Ward Three, the watchdog, galloped in, tripping over the carpet and losing his footing in its heavy folds. He had a dirty femur in his mouth, which he dropped at the Professor’s feet.

“Curses,” said the Professor. “Foiled by a retriever.”

“Oh, I’ve solved it,” said Green. “This one shoots them and this one buries them.”

“Hooray!” said Miss Peacock, clapping.

“Take them away, fellows,” I said, and the cops hustled out Johnny Stomp and Professor Plum. Green followed, watching the two unlikely cohorts being stuffed into a black maria for the trip to jail.

“Holy smokes,” said Green. “Politics sure makes strange bedfellows.”

THE END