As Don Johnson made his way through the yard of his Elkins Lake home, he paused to admire the trees, the bushes, the eaves of the well-appointed homes dripping with festive lights, the electrified manifestations of a robust Christian superiority. “If only I had had snow trucked in from Houston at taxpayer expense,” he thought. “No one’s looking at the books these days.”

That was because he, Don the Don, had villainized all those who displayed a bent for the unclean thinking that leads to insurrection.

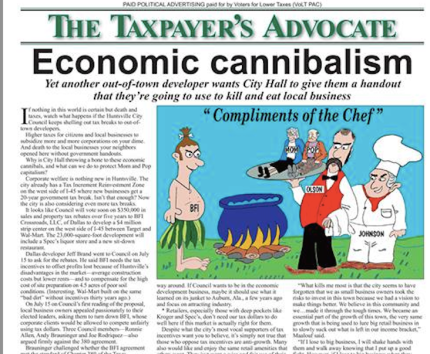

“We, the movers and shakers, we rule here unchallenged for the glory of Almighty God,” said Don to himself. “Is there not now a Hobby Lobby and might there not soon be an Academy and a Chick-fil-A? Is that not my doing along with Buxton Consumer Analytics of Fort Worth, Texas?”

Then a mist rose from a Nativity Scene. In it, Don soon could discern a face, which he thought he might recognize from portraits hanging in the halls of Huntsville’s back rooms. It was not angry or ferocious, but it looked at Don as it had while Don sat scheming beneath its portrait, sternly and with unquestioned authority. The hair of this dour face was stirred, as if by breath or hot air, and, though the eyes were wide open, they were perfectly motionless. That, and its livid color, made it horrible.

As Don stared fixedly at this phenomenon, it was a Nativity Scene again. Yet now the Baby Jesus seemed to be smiling ever so slightly. Don wasn’t sure why, but he felt uneasy. What was that baby up to?

Don entered his home and felt instantly safe and warm. He forgot all about the strange spectre on the front lawn. He had married well, raised a family, and his home was bright and full of love. Yes, indeed, the Lord had smiled upon Don Johnson.

Yet, as the clock on the wall chimed twelve that night, Don awoke with a start, mistaking the toll of bells for gunfire.

“Lanny Ray!” he shouted.

“Go back to sleep, Don,” said his sweet and gentle wife. “Lanny’s not the crazy one; that’s his ex-wife. The courts said so, and I heard it from somebody at bunco.”

“Right,” said Don, adjusting his night cap and settling back into his comfy bed. “But they’re all armed, you know. AK 47s and what have you. Even George Russell supports the Second Amendment.”

“Good, he’s a constitutionalist,” Don’s sleepy wife said. “Just what you always wanted.”

She was fast asleep again when Don heard from the floor below a clanking noise as if someone were dragging a heavy chain across the kitchen tile.

“It’s humbug!” said Don. “I won’t believe it.”

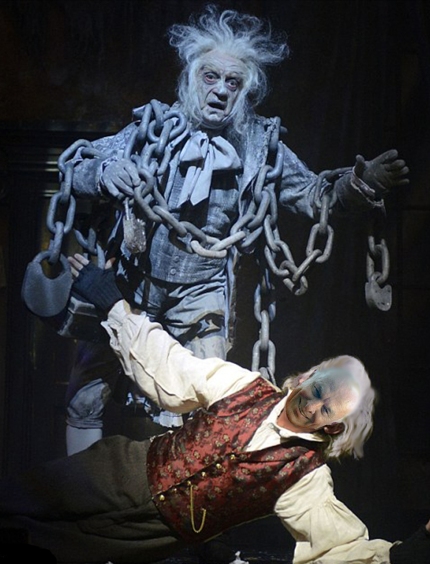

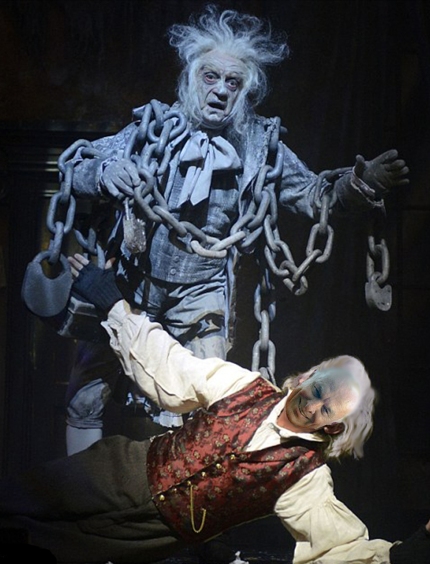

His natural pallor blanched further, when, without a pause, it came through the bedroom door and passed into the room before his eyes. The same face: the very same. In its suit with the wide lapels and the wide chevron tie. The chain he drew was clasped about his middle. It was long, and wound about him like a tail; and it was made of cash-boxes, keys, padlocks, ledgers, deeds, and heavy purses wrought in steel.

Though he looked the Phantom through and through and saw it standing before him, though he felt the chilling influence of its death-cold eyes, Don was still incredulous, and fought against his senses.

“How now!” Don said. “What do you want with me?”

“Much!”

“Who are you?”

“Ask me who I was.”

“Who were you then.” said Don.

“In life, I was Ed Sandhop, Gibbs overseer.” Don invited the ghost to sit and he sat as if he were quite used to it. “You don’t believe in me,” observed the Ghost.

“I don’t,” said Don. “And I have no time for you this Christmas Eve. I’ve spent over five thousand dollars in gifts and must make the rounds to receive the thanks and fealty of the little people who so depend on a nod from me from time to time to be reassured of their worth.”

The Ghost sat perfectly motionless, its hair, the legs of its trousers, and the tassels on its loafers were still agitated as by the hot vapor from an oven. “Do you believe in me or not?”

“I do,” said Don. “I must. But why do you come to me?”

“If a spirit goes not forth in life, it is condemned to do so after death. It is doomed to wander through the world—oh, woe is me!—and witness what it cannot share, but might have shared on earth, and turned to happiness!”

“You are fettered,” Don said. “Tell me why?”

“I wear the chain I forged in life,” replied the Ghost. “I made it link by link, and yard by yard, fifty-seven years; I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it. Is its pattern strange to you?”

Don trembled more and more.

“Or would you know,” pursued the Ghost, “the weight and length of the strong coil you bear yourself? It was full as heavy and as long as this, three Christmas Eves ago. You have labored on it since. It is a ponderous chain!”

Don glanced about himself, expecting to find himself surrounded by some fifty or sixty fathoms of iron cable. There was nothing.

“Perhaps, jealous Phantom, you miss in death what I now control,” Don said. “To frighten me out of my rightful role, that might be more your mission than the merciful one you claim.”

The Ghost, on hearing this, set up a cry and clanked its chain hideously.

“But you were always a good man of business, Ed,” faltered Don, who now began to apply himself to this in hopes of banishing Sandhop and returning to an uninterrupted sleep.

“Business!” cried the Ghost, wringing its hands. “My own life was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business.”

Don smiled with condescension, realizing that this Ghost had misunderstood him completely. Sandhop may have been a poor Christian—if that was indeed what he was confessing—but Don had a reserved room in his Father’s Mansion. He was sure of it.

“Wipe that sickly smirk from your visage,” the Ghost bellowed and rattled his chain. “It reveals the unseemly and unchristian thoughts that seem to circumnavigate your small mind.”

“Don’t be hard upon me, Sandhop! Pray!” said Don.

“You will be haunted,” resumed the Ghost, “by Three Spirits.”

“I—I think I’d rather not,” Don said.

“Without their visits,” said the Ghost, “you cannot hope to shun the path I tread. Expect the first when the bell tolls One. Expect the second at Two, the third when the last stroke of Three has ceased to vibrate. For your own sake, remember what has passed between us.”

The apparition floated through a closed window and upon the bleak, dark night. Don went straight to bed. His wife stirred, half awake. “What’s wrong, honey? Can’t you sleep?”

Don grumbled about a bad dream, a talking ghost, the fault, no doubt, of an undigested apple-dumpling.

His wife yawned. “That’s Melville, dear,” she said. “You mean ‘an undigested bit of beef, a fragment of an underdone potato.’ No need to worry. There’s more of gravy than of the grave in what you saw.”

THE CLOCK STRIKES ONE

Don slept through the chime of the clock but awoke feeling someone pulling on his big toe. In the dim light from the frosty moon let in by his window, he saw a being with wild hair. He sat bolt upright in bed. “Intruder!” he shouted or thought he had, yet his wife remained asleep.

Don leapt from the bed as the Spirit beckoned him to the window. It was a strange figure—like a child, yet not so like a child as like an old man, viewed through some supernatural medium. Its hair, which hung about its neck, was white as if with age; and yet the face had not a wrinkle in it. It wore a denim shirt and filthy, worn blue jeans. Its bare feet were shod in sandals, despite the cold outside, and its toes were long and gnarled, the toenails split and dirty. It cackled, grasping Don’s soft, clammy hand as it flew with Don through the window, which had flung itself open in anticipation of their flight.

“Unhand me, you crazy fool, you George Russell,” said Don as he and the Spirit drifted over the rooftops of Elkins Lake. “What do you want of me at this hour?”

“I am the man who loves Huntsville most of all,” said George. “I am the Ghost of Huntsville’s Christmas Past.”

They lighted within in a woodland home and Don recognized it instantly because Sam Houston himself stood in the middle of the scene, making merry with his family and friends while house slaves waited on them hand and foot.

Despite being aware that he was clad only in pajamas, Don broke free from George Russell and hurried to greet the Great Man, the one who now stood in concrete sixty-seven feet tall on the interstate highway and who looked like a big glowing dildo at night from six miles out.

“Don’t bother, idiot. He can’t see you,” said a voice behind him, one he recognized from just an hour before. Don turned to see Sandhop and his chains seated in a wooden chair against the wall.

“This isn’t how this is supposed to work,” Don said. “I’ve read my Dickens. You disappear at the end of the first part.”

“I’m directing this scene,” George said, “and who better to narrate a Huntsville history lesson but the Gibbs Mafia’s greatest and most feared consigliere?”

Don took a seat next to Sandhop’s ghost, as it rolled its large transparent eyes at George’s foolery, and watched the Houstons’ rustic Christmas unfold.

“Sugar is twelve dollars pound this year, thanks to the War. Too bad we didn’t think to hoard it at the dry goods store,” the Spectre said. “We could have marked it up another two bits.”

“Even the Houstons couldn’t pay that price,” George said.

“Houston was as poor as the rest of us,” grumbled Sandhop’s ghost. “We didn’t grovel at his celebrity until much later. Drunkard, Indian lover, Union sympathizer that he was.”

“What are we doing here, spirits?” Don said. “What am I supposed to learn from this visitation?”

“Who do you see in this room, Johnson?” Sandhop said. “I see the old families of Huntsville, the children of those who erected the first trading post and welcomed the first stage coach line.”

“I see,” said George, “the rise of an enlightened society, a small but progressive city on seven hills, just like Rome, which might have been the seat of government rather than home of the nation’s largest penal system and a public diploma mill.”

“I see a cash cow,” said Don. “Or calf. The city is young.”

Then Don found himself in a large stately home across the street from the present-day Sam Houston Memorial Museum. It was crammed full of all manner of knickknacks, antiques, books and other junk. Lots of junk, some of it obscene. A crazy person lived here. Clearly.

“What is this place?” Don said. “And why are we moving so quickly from scene to scene without the proper transition?”

“It’s called the quick cut,” George said. “Very popular since MTV. Nobody’s got the attention span to hang out in 1862 for a whole hour. So now, let’s talk about me.”

“So this is your house?” said Don, doing a quick appraisal of the furnishings.

“I’m going to turn it into a museum,” George said. “And they won’t like it.”

“Who?” Don said, hoping soon for another “quick cut” right back into his bed.

“The Gibbs, the Smithers, their offspring and descendants, Joe Smythe, the shot caller from New York, the one who had me falsely arrested for protecting my trees,” said George, and then he gave Don Johnson a tour, ending in a room full of pots made by Gibbs slaves, just a portion of his vast holdings of Walker County history. “You know, Mary Laura insists her people didn’t own slaves.”

Don would have agreed that George’s many collections were impressive. For example, these simple ceramic pots, which filled a table nearly a football field long. They had been inscribed, before they were fired by slave hands, with the date of their making. Beyond these walls, on land cleared by men and women who had been bought and sold like livestock, Huntsville’s first plantations were built. Don had never given this any thought, but now the plantation business model—the huge profit potential afforded by free labor—charmed him. Here was something to commend Huntsville’s history after all.

He looked George in the eye as he and this wild-eyed, sex-crazed spectre shared a moment of clarity. Don smirked. “You’re just like me,” he told the Ghost of Christmas Past. “Weathly, white, entitled. But you wouldn’t hoard this shameful pottery if it were your own family’s dirty secret, would you?”

Then Don found himself on his knees in front of Black Jesus in Oakwood Cemetery. He looked up into the tarnished face of Christ. “Dear Lord, what was my take-away in that last scene? I must have missed it.”

“Yeah, I don’t know whose idea it was to let George direct that segment,” sayeth Black Jesus. “Rise, Don Johnson, and listen. First, you were supposed to get that the Gibbs founded this town and they still own it. It rankles their settlers’ souls that George has preserved more of their history than they have, because it’s not his to buy and keep. He’s not entitled to Huntsville’s past, present or future. And neither are you.”

“Me? Pray what did I do, Black Jesus?”

But, though He smiled ever so slightly, the Lord was silent.

THE CLOCK STRIKES TWO

Don woke up in his own bed as the clock began to chime, and just as he was ready to dismiss the previous hour and sleep willfully through the next, a petite figure appeared at the foot of his bed, a short, trim feminine form of post-menopausal age. She wore a whistle around her neck, which she brought to her lips and blew. Its shrill call had him on his feet before he knew it.

“Why are you still in bed? There’s so much to do!” this determined spectre said. “Jane is counting on you.”

Don gathered the bedclothes about himself and glanced over at his wife to make sure she was still asleep. “Nancy?” he said sternly to the ghost. “Nancy Franklin? What are you doing here?”

“I’m the Ghost of Christmas Present, and I’m so proud that Ed Sandhop entrusted me with this hour of his program. So get up!”

Don barely had two feet on the floor when, head still spinning, he found himself in a crowded room in a home he recognized. Again, he was self-conscious at being under-dressed and without his wife, who, many joked—behind his back, of course—was his only “human credential.” Don often had to fake the warmth and interest in others that seemed to come naturally to her.

“Maybe you’re a sociopath,” said the Ghost of Christmas Present, who must have read Don’s thoughts. “But anyway, I’ve got things to do, so you go sit over there with Ed Sandhop. They can’t see him, either.”

The Ghost of Sandhop barely acknowledged Don as he sat down. “Here we are again,” said Don, hoping Sandhop would make conversation. “What now, Spectre?”

“There’s that smirk again,” Sandhop said. “I urge you to get before a mirror and practice something pleasing and subtle. You really would shudder to see yourself on the television.”

Don stopped smiling and scowled, looking at all the party bustle. “Wasn’t I invited?”

“This year,” Sandhop said. “But you’re losing ground. You know that, don’t you? You’re at least that smart, I hope.”

Don was reminded of the Night of the Long Knives, the first city council meeting after the Nov. 5, 2013, city election. Two newcomers, both from Elkins Lake, took their seats at the dais and the incumbent rubes took over, nominating one of their own and ousting Don from his post as mayor pro tem. “It’s not my fault,” Don said.

But Sandhop’s ghost sat silently, gathering a length of chain in his hands much like a consigliere might prepare a garrote for use.

“Okay, so it is my fault,” Don said quickly, though he was sure that it wasn’t, but the Spectre let his chains slip through his hands. Don leaned closer. “But why is it my fault?”

The sigh of a spectre is a chilling sound, a deep, hollow whistle on a cold, icy night. Don shivered, waiting for Sandhop’s ghost to speak.

“You’re arrogant yet weak and poor of judgment, and not very bright to boot,” the Ghost said. “So all your clumsy schemes and machinations are transparent for all to see. And look what’s happened! Public discussion! Insurrection! Ronnie Allen!”

“I won’t be accused of transparency, sir! I don’t care how fearsome you were in life and are now in death,” Don said. “Look, I menaced lots of people, I got them fired, I made deals, I maneuvered. I swelled our ranks, adding several worthy movers and shakers to fend off the previous council and all those who fancy leadership without our permission.”

A spectre’s laugh is perhaps even more frightening than its scowl or sigh. Its chuckle rolls over slowly, laboriously like the cold and massive engine of a war machine.

“Movers and shakers,” said Sandhop. “The term is comical to our ear. What do you village idiots think you move and shake? Your sphere of influence is the size of a farthing, whereas the Gibbs are the largest landowners in all of Texas. Surely you know that.”

Don faltered again. He knew only his own worth and a little of the portfolios of his rich closest associates.

“This is a town of a mere twenty-eight thousand free souls and only an eighth of them vote,” the Spectre resumed. “This is how it has always been. And so it has always been that the largest export of our city is parolees. All over the world, one says, ‘Huntsville, Texas’ and it means prisons and the busiest death house in the free world. Good for tourism, I’d say.”

“Are you not Little Eddie Sandhop, the one who worked his way up from bottom to top?” said Don. “If something’s rotten in Huntsville, it’s your fault, not mine.”

“Back in my day, we knew how to keep the rabble calm and at bay, but you have increased their numbers by increasing your own, by admitting all into the inner circle who hate who you hate and support your retail schemes, ” Sandhop said. “That has never been the golden key.”

“Common purpose, soldiers in arms. Do you say that isn’t how it’s done?” Don said incredulously.

The Ghost cast its vacant eyes over the convivial scene. “Who are all these people? That crook over there, the pole dancer and the hairy-faced redneck over here, that loud mouth constructioneer, those grasping harlots, these angry and crass low-church Christians. The Gibbs are a refined and worldly people. Where did you come upon these rustics and lickspittle?”

“They want the same thing you do, Ed,” Don said.

“They do not,” said Sandhop’s Ghost, pointing his ghostly finger. “We do things one way around here and everybody knew it, or, alas, they did.”

Then Don, watching his near future unfold, brightened as he saw himself enter the gathering with his wife on his arm. Everyone turned to greet them.

“See, they like me,” Don told the Ghost. “They really like me.”

“Zeus’s beard,” the Spectre said wearily. “They’re just being civil.”

THE CLOCK STRIKES THREE

At the chiming of the clock, someone sitting in a chair near the bed struck a match and lit a cigarette. Don watched its red glow intensify as the smoking spectre took a deep drag.

“Jack Wagamon?” Don whispered fearfully. “Is that you?”

The ghost began hacking and snuffed out the cigarette. “Actually, I don’t smoke, but I thought it would be a nice touch. Turn on the light by your bed.”

So Don flipped on the light and squinted at the ghost in the chair. He was a young man in a trench coat and Forties fedora pulled down over his eyes.

“Show yourself, Spectre,” Don said tremulously.

“I can’t,” said the Ghost. “It’s my mother. She couldn’t handle the scandal if it got out.”

“What do I have to do with that?”

The Spectre smiled. The part of his face Don could see was Dick Tracy handsome with its square jaw and chiseled manliness. “A lot, councilman. Now out of bed and on your feet. One last stop.”

“I won’t go with you unless you reveal yourself,” Don said.

“They call me Fractal Bob,” said the Ghost. And just then a gorgeous blonde gun moll popped in, standing behind Bob with a ghostly pistol pointed at Don’s head. “And she is Carissa.”

“You heard him,” Carissa said. “Get up.”

Don gladly obeyed.

“You’re the ghosts of Christmas Future, I presume,” he said as he found himself with his two companions in the middle of a chilly fog. All he could see, aside from their stylishly dead silhouettes, was his bare feet on turf grass. “What is this place?”

They began to walk through the fog until it cleared, revealing a large, half-finished brick school house. Don knew this place, and he began to smile.

“Knock off the creepy smirk, Buster,” said the beautiful gun moll.

“This is Gibbs land and this is a new school,” Don said. “The bond issue must have passed! So when will the new middle school be finished?”

“It won’t be,” said the ghost of Fractal Bob. “Typical Huntsville. The school hired an unqualified contractor who had cost overruns out the ass and the district ran out of money.”

The two ghosts led Don inside the half-finished structure, where weeds grew knee high from cracks in the concrete foundation. “But look,” Bob said, “they woulda had this bitch wired for hundreds of plugs. Just what you all wanted.”

Don and his ghosts popped in and out of every section of town so that Don could see the decay in essential services and loss of the city’s inner charm. “The hospital only takes inmates now. Civilians have to drive to Conroe or Madisonville,” Bob said, as the three of them hovered above the interstate. “You should see Madisonville and New Waverly these days. Crazy growth there, but a shit ton of our local businesses failed, thanks to you and your tax breaks to chain and big box stores.”

“And the Huntsville Item folded,” Carissa said.

Don clapped his hands with glee. “See, there’s a silver lining in every bad situation. Pray tell, Spectre, what deserving scourge befell them?”

“They kept running George Russell’s letters and then one day they plastered George all over the front page,” she said, “and you all convinced the local businesses that were left to cancel their advertising.”

“Merry Christmas to me! That’s wonderful,” Don said. “I suppose somebody started a new paper more friendly to our cause.”

“Yup,” said Bob, “but it died too, just like the Huntsville Morning News. They didn’t know shit about running a dying industry. And without a newspaper to read the news from every day, KSAM went silent, too. So now Average Joe doesn’t even know who’s county judge or who sits on city council. The latest crop of movers and shakers have all moved to The Woodlands.”

“Maybe without a local newspaper to make them feel important, they realized they were just the little kings and queens of nothing,” Carissa said.

“You smug spectres, how is it you have the nerve to be so irreverent, so blasphemous and so impudent?” Don said.

Then Don found himself again enshrouded by fog, and his spirit guides were gone. A figure approached, striding deliberately at Don as he stood there shivering in his fog-dampened jammies. Just as he was about to call out to the figure, he recognized it. Ed Sandhop, now without chains or other supernatural encumbrances.

“Who’s left then?” Don asked Sandhop, “if my movers and shakers are all gone?”

“We are,” Sandhop said. “And the people who are content to do as they’re told.”

“What has become of my family? What about my church and Alpha Omega Academy?”

“All fine,” Sandhop said. “All as quiet as church mice. No more fighting, no more factions, no more letters to the editor. No more obstacles. We have one way to run this town and you couldn’t handle it.”

“But what of city council?” Don said. “I so dreamed of becoming mayor one day.”

Sandhop smiled as though he were enjoying a private joke. “You’re not on the list,” he said. “Sorry.”

Then Sandhop extended his arm and pointed his finger, directing Don into the fog, and Don was terrified the Phantom had condemned him to endless wandering. “No, Spirit! Oh no, no!”

The Phantom’s finger pointed the way unrelentingly.

“Spirit!” Don cried, clutching at its sport coat. “Hear me! I am not the man I was. I can be more sinister and controlling; you know I have it in me. I can get better at manipulating the course of events. I can cast out the rubes and the peasants from the inner sanctum while protecting the likes of you and me. Jane, she once believed in me. Ask her now for some recommendation of my worth.”

But the Phantom wavered not.

“Surely you’re not saying Jane is nothing more than overseer herself, that her chain is as long as yours and mine,” Don said.

The finger.

“Why show me this, if I am past all hope?” In his agony, Don caught the spectral hand. It sought to free itself, but he was strong in his entreaty, and detained it. The Spirit, stronger yet, repulsed him.

Holding up his hands in a last prayer to have his fate reversed, Don saw an alteration in the Phantom’s face and dress. It shrunk, collapsed, and dwindled down into a bedpost.

THE END OF IT

Don awoke with a start in his own bed. His dear wife lay beside him and he shook her awake to share the revelation that had come to him over the course of these three terrible visitations.

“Where’s some paper and something to write with!” Don said. “I must make a hit list right away. I’ve got to be everything Ed Sandhop was and then some. Hurry, help me! Or the whole town is going to hell in a hand basket. I have seen it!”

“I’ll make some coffee,” she said.

Don had a dozen names on the hit list before the coffee was ready.

“Shouldn’t you be buying turkeys for indigent families or sending Christmas cards to the naysayers, Don?” his wife said.

“I’ve got to call the churches and Jane, Sally, who else? I can’t be expected to fill out this new hit list by myself. You know those naysayers have one and we can’t be without one, either,” Don said. “Wait, I’m sure Jane’s got names left over from Sandhop’s day. The list just needs to be updated.”

Then Don’s body suddenly felt very heavy, weighted by coils of iron. He looked down and saw the yards of heavy links that Sandhop had been schlepping around in Don’s wretched dreams.

“You totally missed the point,” his wife said. “Ed Sandhop gave his life to the Gibbs when he could have done anything, gone anywhere, been anybody. And here we are, and you’re doing the same thing. Don, we’ll always be newcomers here if we stay here twenty more years.”

Don felt on the verge of tears. “But I’m a mover and a shaker,” he said. “If we’re not ‘in’ we’re ‘out.’ If we’re not ‘in,’ we might as well be named Wagamon.”

“What does that matter?” his wife said. “Huntsville is a pretty place where good people can live a simple and uncomplicated life. There are lovely people here and fun things to do, things that accomplish next to nothing but uplift the soul or gladden the heart. There is so much that people like us can do to make this a better place, a happier place, a caring place for those less fortunate. Live and let live, Don, and you set yourself free. You’ll be saved once you realize you have nothing to prove.”

So Don did it; he stood and let the chains of ambition and discord fall from him, and his soul soared. His wife beamed at him with the love and joy of their first days together.

“God bless us, everyone,” she said.